By: Patricia Spilman | Posted: February 25, 2016 | Updated: April 5, 2023

This article describes the top modifiable Alzheimer’s risk factors, and explains what you can do to reduce them.

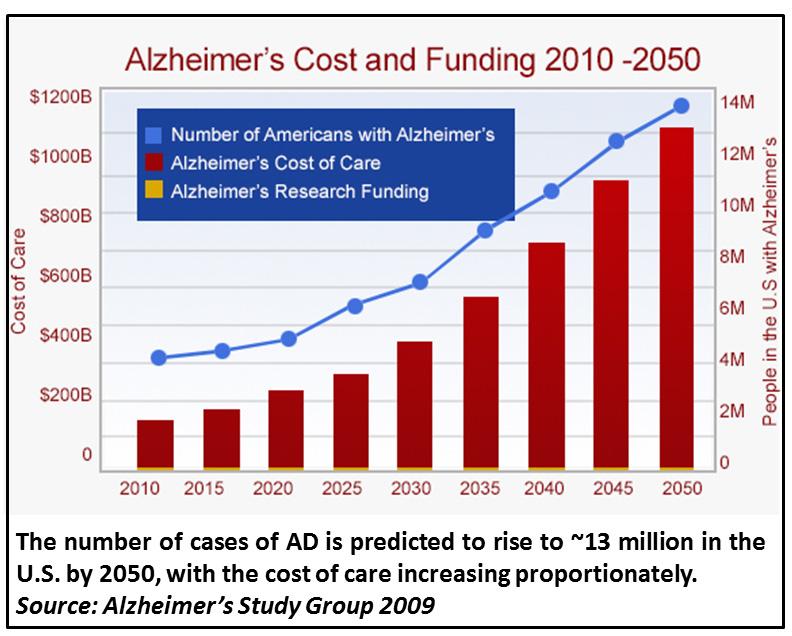

As the US population ages, the number of Americans afflicted with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is expected to rise from the current ~5 million to ~14 million by 2050. The annual cost of over $200 billion does not begin to reflect the heartache to the families affected.

Almost all of us would like to know how to lower our risk of developing Alzheimer’s, especially as currently there are no truly effective disease-altering treatments for this type of dementia.

To lower the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, or at least to delay the onset, first it is critical to identify the leading risk factors, and determine which are modifiable (i.e., those that can be addressed and reduced). In the case of AD, the single greatest risk factor is advanced age. Current statistics show that in the United States, approximately 50% of people over age 85 will develop AD. Yet living to an advanced age is a risk that most of us are certainly willing to take.

To approach risk reduction effectively, it is important to know that the underlying causes of AD are many, debated, and individual. Much of what is diagnosed as “Alzheimer’s disease” is dementia (a general term for loss of cognitive function resulting in impairment of daily activities) that does not strictly meet the criteria for AD. There currently exist very advanced and accurate diagnostic tools for diagnosing AD and distinguishing it from other causes of dementia (e.g., vascular disease, untreated central nervous system infection, depression, medication cross-reactions or mix-ups and even severe vitamin deficiency or chronic dehydration). These diagnostic tools are not always available to individuals, however, typically due to insurance limitations.

Different forms of Alzheimer’s: Genetics at work

There are several forms of AD. One relatively rare form is known as “familial AD” because it is caused by a gene mutation that runs in families. Also called “early onset” AD, its symptoms typically first appear before age 60. The character in the book “Still Alice” written by Lisa Genova, later made into a movie by the same name, had familial AD. Discussion of the genetics of familial AD is outside of the scope of this article, but briefly, they are rare changes in a gene sequence that lead to alterations in function or production of certain proteins in the brain. These mutations are often named after the geographical location of the families in which they are found (“Swedish”, “Indiana”, “Dutch”, “Arctic”). Almost invariably they lead to increased production of a small protein called amyloid beta (Abeta) that is found in the amyloid plaques that characterize brain tissue of AD sufferers.

Genetics cannot be changed and therefore are not typically a modifiable risk factor. In fact, it can be a traumatic decision for an individual to ask that their genetic risk for familial AD be ascertained when they know this form of AD runs in their family. Clinical trials underway right now for drugs that target the protein abnormalities in these patients could lead to treatments for familial AD.

Most cases (~95%) of AD are not familial, but “sporadic” or what is often called “late-onset” AD (LOAD), with signs and symptoms first appearing after age 65, and typically much later. Genetics can still play a role in an individual’s risk of sporadic AD, for example in the case of apolipoproteins (ApoEs). ApoEs bind oil-soluble molecules such as fat and cholesterol and transport them throughout the body and brain, where this function is critical for supporting the health and function of cells.

ApoE genes come in four forms (alleles), and every human being has some combination of these. Most individuals have “epsilon 3” or ApoE e3, and a much smaller number have what is thought to be the protective ApoE e2 form (ApoE e1 is extremely rare). Some individuals, however, have an increased risk for sporadic AD due to having (“expressing”) a form of apolipoprotein called “epsilon 4” or ApoE e4.

While only about 15% of the population expresses ApoE e4, approximately 50% of AD patients express it, and the risk conferred by ApoE e4 is greater for women than men [1]. Yet many individuals who express ApoE e4 do not develop AD; studies are underway to discover how these people resist its development. While ApoE form is a genetic risk factor, it is has been seen that the health and lifestyle choices people make can greatly reduce the impact of having ApoE e4 (in contrast to the familial Alzheimer gene whose impact cannot be mitigated unless and until an effective drug or other disease-altering treatment is discovered).

Modifiable Alzheimer’s Risk Factors

Many of the risk factors for sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease are not genetic and therefore are potentially modifiable by everyone.

To narrow the focus on the top risk factors, the authors (Xu et al.) of a 2015 study in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry utilized meta-analysis of more than 16,000 studies, finding 323 studies describing 93 risk factors that met their very strict criteria for ranking risk. They found “grade 1” evidence that the top modifiable risk factors for sporadic AD, in no particular order within this top group, are: high body mass index in mid-life, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, carotid atherosclerosis, high homocysteine, depression, frailty, low diastolic blood pressure, and low education attainment.

Many excellent studies have revealed other potentially modifiable risk factors that may not be in the top nine, but are important nonetheless. These include chronic stress, lack of physical activity, smoking, poor sleep quality (including sleep apnea, the cessation of breathing while sleeping) and even poor oral hygiene. All of these risks should be considered, although not all will be discussed here.

High Body Mass Index in Mid-life

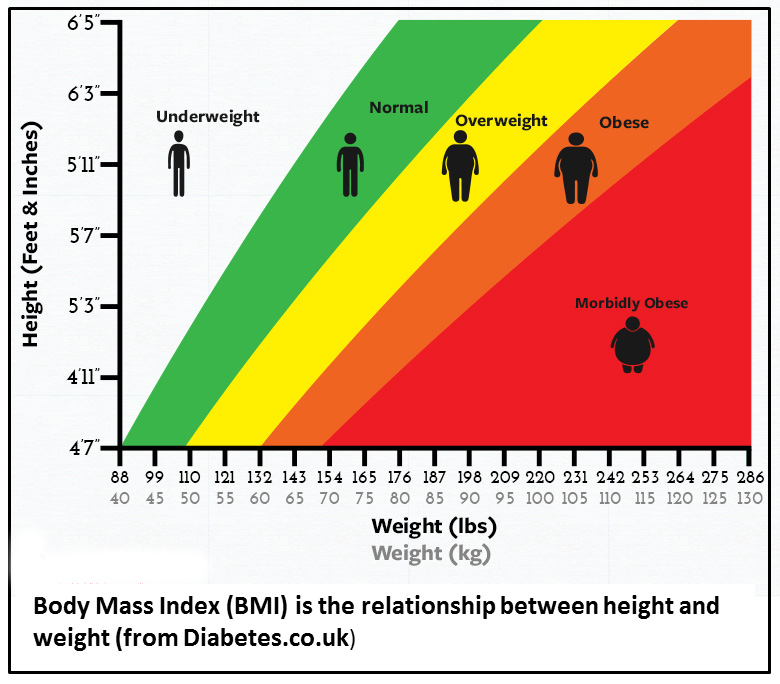

It is undeniable that an increasing number of Americans are obese – they have a high body mass index (BMI). BMI is simply weight (mass) in relation to height. A high BMI persisting from youth or emerging in mid-life is a reflection of the presence of at least two modifiable lifestyle factors, most significantly lack of exercise and poor diet.

It is undeniable that an increasing number of Americans are obese – they have a high body mass index (BMI). BMI is simply weight (mass) in relation to height. A high BMI persisting from youth or emerging in mid-life is a reflection of the presence of at least two modifiable lifestyle factors, most significantly lack of exercise and poor diet.

When it comes to lowering the risk of developing AD, the importance of regular exercise cannot be overstated. Among the many benefits of exercise is the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor [2]. As the name suggests, this is a factor that supports survival of the cells in the brain that store memory and communicate information.

Type 2 diabetes

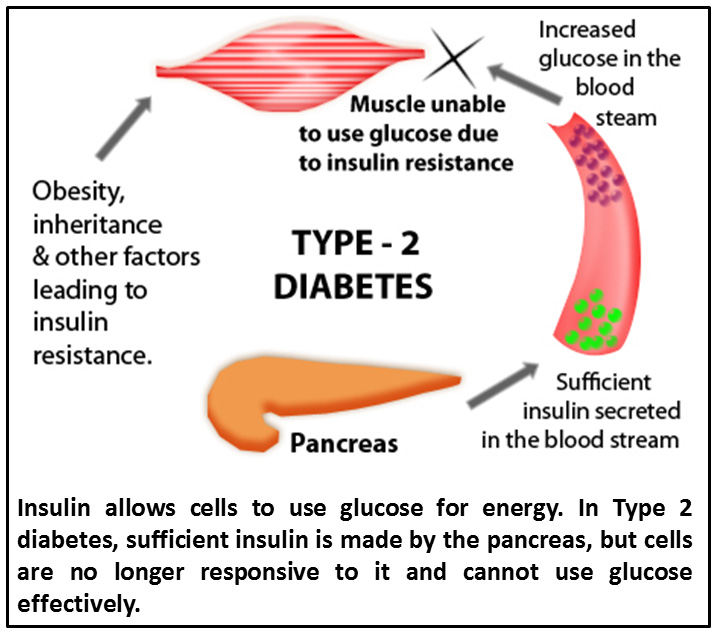

According to the National Diabetes Statistics Report 2014 published by the Center for Disease Control (CDC), the number of cases of Type 2 diabetes is rapidly increasing in the US population. While Type 2 diabetes can run in families, the development of this disease is closely associated with high BMI. Type 2 diabetes differs from Type 1 diabetes in that the pancreas continues to produce the insulin that is required for cells to utilize glucose for energy, but cells are no longer responsive to it – they are “insulin resistant”. In Type 1 diabetes insulin production is impaired. Type 2 diabetes is often the result of continuous exposure to high levels of the sugar glucose.

According to the National Diabetes Statistics Report 2014 published by the Center for Disease Control (CDC), the number of cases of Type 2 diabetes is rapidly increasing in the US population. While Type 2 diabetes can run in families, the development of this disease is closely associated with high BMI. Type 2 diabetes differs from Type 1 diabetes in that the pancreas continues to produce the insulin that is required for cells to utilize glucose for energy, but cells are no longer responsive to it – they are “insulin resistant”. In Type 1 diabetes insulin production is impaired. Type 2 diabetes is often the result of continuous exposure to high levels of the sugar glucose.

Lowering BMI with healthy eating habits including reduction of consumption of simple carbohydrates/sugar and increased exercise lowers the risk of developing both Type 2 diabetes and AD. Even in the absence of high BMI, accurate early diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes and proper treatment focused on management of blood sugar is critical to reduce the risk of AD [3].

Hypertension

Many of the top modifiable risk factors for AD are interrelated. For example, while hypertension (high blood pressure) may exist in the absence of Type 2 diabetes, the presence of Type 2 diabetes increases the chance of a person having hypertension. Additionally, literally hundreds of studies support the relationship between high BMI and hypertension.

Overlap in the risk factors does at least allow for efficiency in addressing them: exercise, healthy diet, and early/effective treatment for either Type 2 diabetes or hypertension. Hypertension itself can often be managed with medication, and optimizing this treatment may likely reduce the risk of later AD.

Carotid atherosclerosis

Most vascular disease exacerbates loss of cognitive function. There is a form of dementia called “vascular dementia” that is due to poor blood circulation in the brain. Quite often, patients have signs of both vascular dementia and AD.

Most vascular disease exacerbates loss of cognitive function. There is a form of dementia called “vascular dementia” that is due to poor blood circulation in the brain. Quite often, patients have signs of both vascular dementia and AD.

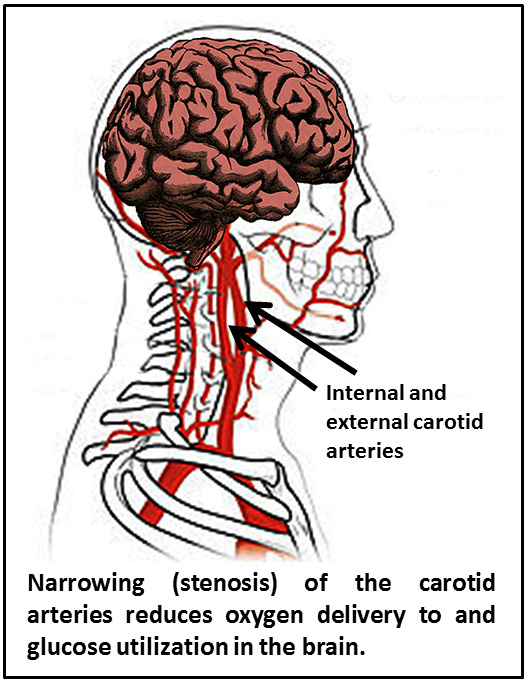

Narrowing of the major vessel that carries blood to the brain, the carotid artery, increases the risk for stroke and AD. Restricted blood flow to the brain results in less oxygen being delivered to the brain and impacts glucose utilization; both of these effects increase Abeta and amyloid production.

Early/accurate diagnosis and treatment of carotid atherosclerosis is critical for lowering the risk of later development of AD [4, 5]. Some of the warning signs are sudden weakness or numbness in the face, arms, or legs, trouble speaking or understanding, sudden vision problems, dizziness, sudden severe headache, numbness or weakness in the limbs, and/or numbness in one side of the face. Surgical intervention to clear the artery or place a stent should improve blood flow.

High homocysteine

Multiple studies have shown a tight relationship between high homocysteine and AD [6].

Multiple studies have shown a tight relationship between high homocysteine and AD [6].

Homocysteine is one of the many naturally-occurring building blocks of proteins called amino acids. Its levels can rise due to poor diet – particularly a diet low in B vitamins – or excessive alcohol intake, as well as other reasons. Homocysteine can injure the walls of blood vessels, inducing accumulation of sclerotic plaque and triggering inflammation. Atherosclerotic plaques contain cholesterol, triglycerides, and cell debris rather than Abeta.

Homocysteine level in blood can be readily ascertained and typically, increasing B vitamins and specifically folate can address this risk factor for AD. Follow-up measurement of homocysteine levels should be done to assure it is adequately lowered by nutritional intervention.

Depression

Depression has myriad underlying causes, many of which overlap with other risk factors for AD. One is chronic (but not acute or occasional) stress which has been associated with increases in another brain tissue alteration found in AD, the formations of tangles of cellular components from neurons.

A new concept to describe the relationship of depression to AD was recently presented in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. This concept was termed “cognitive debt”, and it is the result of repetitive negative thinking (RNT) [7]. One can readily see how obstruction of normal positive thought processes may ultimately affect brain function.

Disrupting RNT and treating major depression can be difficult. The most effective treatments combine pharmaceutical intervention, counseling, emotional support, exercise, and healthy diet.

Frailty

While seeming counter-intuitive considering that high BMI in mid-life is a risk factor for AD, a decline of body mass in advanced age combined with a loss of strength and mobility is a distinct risk factor for AD.

There is some support for the idea that increased frailty is an initial sign of AD. The reasons for loss of body mass with age are many, but clearly maintenance of physical activity and good eating habits throughout life – including eating enough food – are keys to lowering the risk of AD [8].

Frailty is not just low BMI, it is a condition comprising ease of tiring, mood disturbance, osteoporosis, decreased strength, and high susceptibility to illness. Smoking, untreated depression and certainly malnutrition can place one at higher risk for frailty. As people who are frail are often under the care of others, modifying this risk factor requires the help of others in encouraging the frail individual to get some physical activity every day, engage in social activities, treat depression, and establish good nutrition which includes eating adequate amounts of food. Also, dehydration is often associated with frailty, so intake of adequate fluids is important.

Low diastolic blood pressure

In biological parameters, there is usually an optimal range; blood sugar can be too high or too low, and the same is true for blood pressure. Both high and very low blood pressure can impair cognitive function [9].

In the case of low diastolic blood pressure (baseline pressure as measured between beats of the heart), the effect is similar to carotid atherosclerosis: poor delivery of blood to the brain. There are limited pharmaceutical options for treatment of low blood pressure (hypotension), but maintaining good hydration, consuming some salt (restricted with hypertension, but helpful with hypotension), and even wearing pressure stockings are recommended.

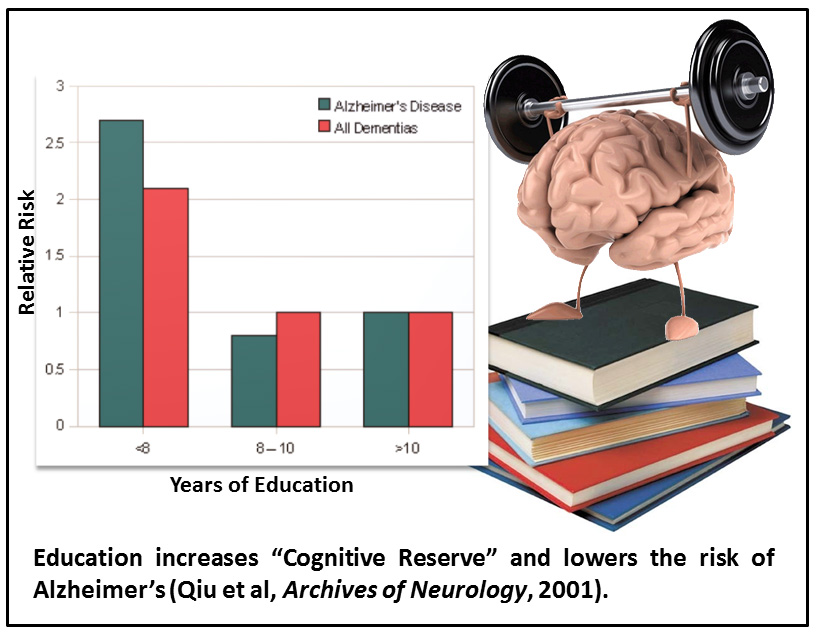

Low educational attainment

Of the risk factors described here, low educational attainment seems to be the odd man out, as it is a lifestyle factor that is not physiological.

Of the risk factors described here, low educational attainment seems to be the odd man out, as it is a lifestyle factor that is not physiological.

However, education in its many forms does have a physiological impact on the brain. It is associated with what is called “cognitive reserve”[10]. This is a term that essentially means the brain has established many cell-to-cell connections so that if some are lost due to the factors described above (and others), relatively normal cognitive functioning can continue.

Addressing this risk factor is arguably the most fun. Individuals who continue to learn, participate, teach, and contribute to society give themselves an opportunity to increase their cognitive reserve and therefore lower his/her risk of developing AD.

Be pro-active in lowering risk

Not all risk for AD can be avoided, of course. We should not think of the development of AD being an individual’s fault.

But an individual who wants to pro-actively decrease their own risk of developing AD will maintain a healthy weight, exercise, have a diet rich in vitamins and low in simple carbohydrates. Lowering risk also requires good medical attention to issues with blood pressure, atherosclerosis, homocysteine levels, and psychological conditions such as depression. A person with a lower risk of AD embraces a life of learning.

Perhaps just as important as what we do for ourselves, we must support the health of others by encouraging a “healthstyle” that lowers the risk of AD – it is easier and rewarding to do it together.

References

[1] Ungar L, Altmann A, Greicius MD (2014) Apolipoprotein E, gender, and Alzheimer’s disease: an overlooked, but potent and promising interaction. Brain Imaging Behav8, 262-273.

[2] Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW (2015) A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Psychiatr Res60, 56-64.

[3] Rasool M, Malik A, Qazi AM, Sheikh IA, Manan A, Shaheen S, Qazi MH, Chaudhary AG, Abuzenadah AM, Asif M, Alqahtani MH, Iqbal Z, Shaik MM, Gan SH, Kamal MA (2014) Current view from Alzheimer disease to type 2 diabetes mellitus. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets13, 533-542.

[4] Wendell CR, Waldstein SR, Ferrucci L, O’Brien RJ, Strait JB, Zonderman AB (2012) Carotid atherosclerosis and prospective risk of dementia. Stroke43, 3319-3324.

[5] de la Torre JC (2010) The vascular hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: bench to bedside and beyond. Neurodegener Dis7, 116-121.

[6] Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Gamaldo AA, Teel A, Zonderman AB, Wang Y (2014) Epidemiologic studies of modifiable factors associated with cognition and dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health14, 643.

[7] Marchant NL, Howard RJ (2015) Cognitive debt and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis44, 755-770.

[8] Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K (2011) Nontraditional risk factors combine to predict Alzheimer disease and dementia. Neurology77, 227-234.

[9] Kennelly S, Collins O (2012) Walking the cognitive “minefield” between high and low blood pressure. J Alzheimers Dis32, 609-621.

[10] Xu W, Yu JT, Tan MS, Tan L (2015) Cognitive reserve and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol51, 187-208.

*Disclosure: The research and opinions in this article are those of the author, and may or may not reflect the official views of Tech-enhanced Life.

If you use the links on this website when you buy products we write about, we may earn commissions from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate or other affiliate program participant. This does not affect the price you pay. We use the (modest) income to help fund our research.

In some cases, when we evaluate products and services, we ask the vendor to loan us the products we review (so we don’t need to buy them). Beyond the above, Tech-enhanced Life has no financial interest in any products or services discussed here, and this article is not sponsored by the vendor or any third party. See How we Fund our Work.